'I escaped Syria like a criminal, and came back a hero'

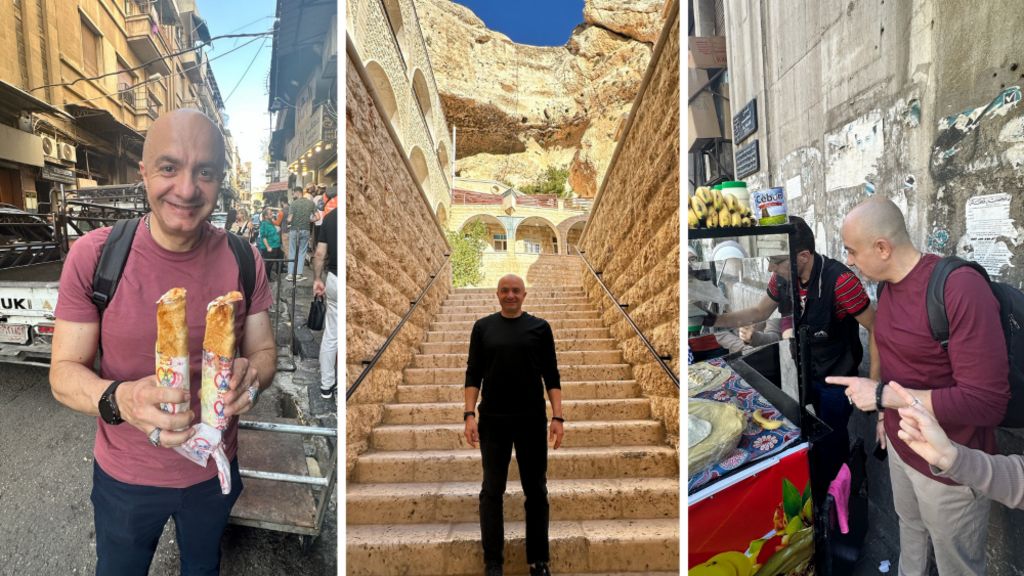

When chef Imad Alarnab fled from Syria to London in 2015, he thought he would never return.

"When I left Damascus, I knew for sure I was on the Assad regime's blacklist. I didn't plan on ever going back, because if I did, I would be either killed or kidnapped."

Yet last month, Mr Alarnab returned to Syria for the first time, after Bashar al-Assad was overthrown by opposition forces last December.

"I escaped Syria like a criminal, and came back as a hero. Assad's blacklist is now our honour list," he said.

Bashar al-Assad had ruled Syria since 2000, taking over from his father Hafez, who came to power in 1971.

A bloody civil war erupted in 2011, after Assad's brutal crackdown on pro-democracy protests during the Arab Spring.

"In 2013, Damascus was filled with Assad's colours. His photos were everywhere, his forces were everywhere. It was really scary," Mr Alarnab said.

"It was more dangerous to carry your own camera than to carry a gun, because they were more afraid of free speech."

Assad's rule had appeared to be secure but a sudden offensive by the Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) opposition group toppled his regime in a matter of days.

"I was scared to go back and find the same Damascus, but it wasn't. It was even better than before," Mr Alarnab said.

"It's a city trying to build itself all over again with a much better image – an image of freedom, of rebuilding, of new government, most importantly without a dictatorship."

Mr Alarnab was a restaurateur in Damascus from 1999 until 2013, when Assad's forces destroyed all of his restaurants in just six days.

Fearing for his life, he fled across Europe to rebuild his life in London, initially working as a car salesman before returning to the kitchen with a pop-up restaurant.

He now runs two restaurants in central London, in Soho's Kingly Court and at Somerset House, and says he feels equally proud to be British as he does Syrian.

"Damascus is the city I was born in. It's the same love I feel for my mother - the old city, the first love.

"I will always be my mother's boy and I will always be Damascus's boy.

"But London is my sweetheart. I rebuilt my life in London. London took me in and loved me back."

While he was in Damascus, Mr Alarnab visited the Cathedral of St George.

George is the patron saint of England, and is believed to have had Syrian roots through his mother.

"I will never become England's saint like St George, but I will always be London's sweetheart," Mr Alarnab said.

"We describe refugees as if they are the source of problems, but we are not. We came from Syria with love, just like St George."

Dr Ammar Azzouz studied architecture in the Syrian city of Homs until 2011, when he moved to the UK to complete his postgraduate studies.

He is now a lecturer and research fellow in geography at the University of Oxford, focusing on issues of architecture and war.

"Syria is still bleeding and the wound is still open," he said, noting the violence targeting communities like the Alawites and Druze in recent months.

"However, we need to dream for a different kind of tomorrow, a Syria built on justice, freedom, dignity and democracy for all Syrians."

'Death was everywhere'

Dr Azzouz was able to return to Syria for the first time in 14 years in March, the first of three visits this year.

"Death was everywhere in Homs. In my street in every building there's a story of forced disappearance or torture.

"I remember seeing a cemetery of graves with numbers, but no names. It's like Homs has become a death world."

The United Nations estimates more than 580,000 people were killed during the Syrian civil war, with 13 million Syrians forcibly displaced.

Dr Azzouz had seen his parents only a handful of times after 2011, and was unable to bring them to the UK to see him graduate.

"To return and see them was absolutely heart-breaking. They live in a very extreme situation.

"The medical system has collapsed and it means people struggle to find medicine, to have proper treatment.

"You can see the war in the bodies of the people, in their eyes, in their homes, and I don't think it will ever leave them."

Dr Azzouz said the Assad regime had "created an enforced silence and the complete absence of public grief".

"Some people want to move on and start a new future, but we cannot move on without acknowledging what happened.

"We need to document the horrors of war, not as a place of constant grief and mourning, but to build a hopeful future."

He emphasised the need for Syrians themselves to lead the rebuilding of their country.

"There is excitement to start reconstruction, but many international companies are rushing for a slice of the reconstruction cake, and see it as an investment opportunity.

"My homeland and my pain are not for profit."

Listen to the best of BBC Radio London on Sounds and follow BBC London on Facebook, X and Instagram. Send your story ideas to hello.bbclondon@bbc.co.uk

(Feed generated with FetchRSS)